nav

How did the Industrial Revolution change the lives of working people in Britain? Five Core Aspects.

The Industrial Revolution (1780-1850) changed the lives of working British people in fundamental ways that can be viewed through five core aspects: disconnection from traditional practices, disciplined labour, gendered divisions of labour and poor living conditions despite higher wages.

At its core, the Industrial Revolution disconnected artisans from their traditional crafts by replacing them with manufactured technology instead of craftspeople doing self-paced work in their own homes or workshops to create products sold locally or to visiting agents. The rise of cheaper manufactured products rendered many rural artisans obsolete, and having little other choice for work, they “(or more often, their children) [….] either worked in factories or catered to those who did.” (Mokyr 2009, p.457). Life before the Industrial Revolution could be difficult for artisans, but the trauma of being disconnected from their (often intergenerational) crafts “must become part of the welfare calculus of the Industrial Revolution.” (Mokyr 2009, p.457).

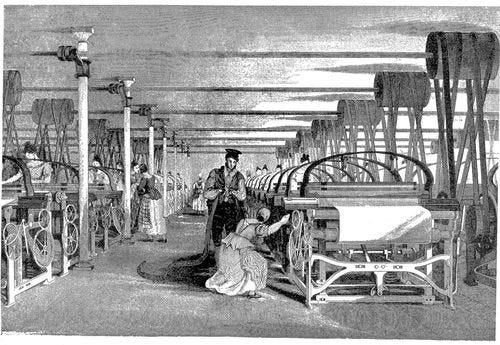

Conditions varied in different industrial environments and periods, with improvements during the 1840s and 1850s. While it could mean consistent employment throughout the year which was often unavailable in rural areas, factory working conditions could be dangerous depending on the job, relentlessly physically demanding and were defined by a clock. This use of a clock to define work hours is a key aspect of industrial factories that changed the lives of British working people by governing their lives and determining their pay, a practice that is arguably still in place today. “Factory discipline of the workforce was instilled not just by the regularity and observance of clock time but also by a mixture of incentives and punishments.” (Morgan 2011, p.13). Conditions in factories could range from harrowing to comfortable or somewhere in between. Some factory owners genuinely cared about the welfare of their workers, and some did not. The Industrial Revolution also created a new class divide in Britain: the ‘bourgeoisie’ (middle class factory owners), and the ‘proletariat’ (urban industrial working class).

Child labour is a defining characteristic of working people’s experiences in the Industrial Revolution and altered the structure of family units. Both primary and secondary sources confirm that children could be regularly beaten and forced to complete dangerous and arduous tasks in mills and factories, often working thirteen hour days. In domestic industry, children did work, but it was with family members and augmented by free time. Long factory hours, however, gave children little time for sleep or leisure and made it difficult for families to bond. The 1833 Factory Act limited work hours in factories for women and children and created some provisions for children’s education but did not abolish child labour.

Gendered divisions of labour are a key change in the lives of working people in Britain. In the pre-industrial domestic textile industry, for example, women usually span the thread and men wove it into cloth, but during and after the Industrial Revolution, men dominated machinated spinning because of its higher wages and the masculine associations with using machinery, whereas women were given menial tasks and/or finished garments in the home. This gender divide cannot be separated from the wider patriarchal society of Victorian Britain that centred men as stronger and more skilled than women, who, although the predominant gender in factories, were seen as physically weaker and requiring protection. “the culmination of this process was the Victorian elevation of the home as a woman’s proper abode, the notion that men and women operated in ‘separate spheres’ and that housework was a feminine activity.” (Morgan 2011, p.15).

The living conditions of working British people during the Industrial Revolution changed dramatically from their previous rural lives. The population increase put strain on cities, who often struggled to cope with the influx. Cities did not adequately invest in proper infrastructure, which created widespread problems in sanitation and influenced the outbreak of cholera in 1830 and 1831. While workers did receive increased wages, the benefits of this were frequently mitigated by the higher food, water, and housing costs in industrial areas. Like factories, living conditions for working British people in industrial areas could be harrowing and life expectancies lower. 19th century writers like Dickens and Engels published works about this topic to raise awareness around ‘the plight’ of working British people, however this should be kept in perspective as conditions could vary throughout industrial Britain and in different periods. Despite the poor conditions, people continued to flock to cities, because “while urban employment may have been risky, rural prospects were perceived to be little better for the unskilled poor.” (Mokyr 2009, p.457).

In conclusion, there is continual debate over whether the Industrial Revolution positively or negatively changed working British people’s lives. While pre-industrial Britain is often unrealistically portrayed as a serene utopia, many rural people often experienced poverty. But many of these same people worked self-paced alongside their own families in an environment with clean air, free drinking water and green spaces. Conversely, factories and mills could undoubtedly have positive aspects and gave many workers the opportunity to better the lives of their families, but countless workers remained in poverty and had a lower quality of life than in their prior rural settings.

Reference List:

This article was originally one of my university assignments, wherein I was required to closely analyse a selection of the weekly readings about the Industrial Revolution and discuss how it changed the lives of working people in Britain. I have listed these readings below. The page numbers refer to which parts of these sources I was required to read and cite in the assignment.

Mokyr, Joel, The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain (New Haven, 2009), pp. 463–5.

Engels, Friederich, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845), Penguin Classics edition (London, 1987), pp. 62–4, 98, 100, 169–70.

The Victorian Web, ‘The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century England — Evidence Given Before the Sadler Committee (1831-1832)’, www.victorianweb.org/history/workers1.html, accessed 17 Dec 2023.

Morgan, Kenneth, The Birth of Industrial Britain, 2nd ed., (Harlow, 2011), pp. 13-15, 15-18.