nav

What can Hildegard of Bingen’s life reveal about the medieval concept of gender?

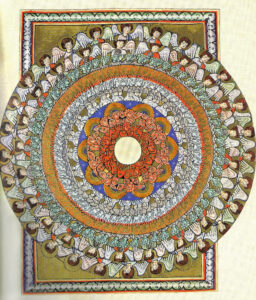

An image from Hildegard of Bingen’s Scivias Text.

Saint Hildegard of Bingen was a medieval Catholic nun, mystic and prophetess who rose to fame through her publication of the visions she experienced throughout her life. While I am not a religious person, I do find Hildegard to be a fascinating figure through which to examine the medieval concept of gender, especially surrounding religion. In this article, I primarily refer to three texts about Hildegard by Atherton, Dickens and Newman which are listed after the article in the references section.

Saint Hildegard of Bingen was an intelligent woman who consciously worked within socio-cultural and religious patriarchal constructs of her milieu to create more agency for herself and other nuns, while simultaneously living with difficult health issues that she used to her advantage.

Two key aspects emerge from her life in regard to what we can be learn about the medieval concept of gender.

Firstly, Hildegard of Bingen used her health issues as a way to strengthen her argument that her visions were real and should be taken seriously by her male contemporaries, instead of letting herself be limited by them.Throughout her life, Hildegard dealt with numerous health issues, and was aware that they were somewhat connected to the visions she experienced (Newman 1985). In the medieval era, women were considered physically and mentally weaker than men, but Hildegard used this to her advantage and stated that had it not been for her frailty, “the inspiration of the Holy Spirit would not be able to dwell in her,’ (Newman 1985, p.167; Dickens 2009). Hildegard transforming her physical health into a strength rather than a weakness through the lens of her religious visions is an important insight into the ways that women, particularly those in similar situations to Hildegard, could navigate and push back against patriarchal constructs and presumptions of gender, health, and religion in the medieval period.

The second key aspect regarding gender is about how Hildegard had her visions validated and created agency for herself by consciously operating within medieval gender norms. Throughout her life, Hildegard consistently referred to herself as uneducated, a ‘poor little female’ and that ‘the words are God’s, not hers.’ (Newman 1985, p.164; Dickens 2009, p.28) At the same time, Hildegard presents her visions as intellectual, a higher form of vision that was typically associated with men, rather than visions experienced corporeally, a lower form of vision associated with women (Freeman 2022). She also writes accounts of her visions in a very calm, collected manner, further indicating that she had not given into “feminine weakness” (Newman 1985).

Hildegard’s self-effacement combined with presenting her visions as intellectual paradoxically validated her further in a society where religious visions were one of the few ways a woman might be able to make herself heard, but nevertheless “while men might perhaps heed a divinely inspired woman, they would have little patience with a mere presumptuous female.” (Newman 1985, pp.164, 170).

By operating within medieval gender norms, Hildegard and other medieval women could push against their restrictions while seemingly denigrating their own intelligence and strength.

This intersects with how Hildegard sought male validation for her visions and prophecy from an influential monk, who then passed her work onto the current pope (Dickens 2009). The pope then gave Hildegard papal approval, which made her famous and influential (Dickens 2009). A few years later, Elisabeth, a young nun who also received religious visions, wrote to Hildegard, and asked her to validate them, which Hildegard did (Newman 1985).

“Just as Hildegard had written in her uncertainty to Bernard, the outstanding saint of the age, so Elisabeth wrote to Hildegard.” (Newman 1985, p.173).

This gives an important insight into how some medieval nuns could have their work validated by a male authority, and then use that validation to create a chain reaction of women validating each other.

In the modern day, a lot hasn’t changed for women in some ways. While women definitely have a lot more agency and freedom of expression than the medieval era, we are still often considered overemotional and irrational in comparison to men, and therefore viewed as unfit for careers that require instinct, decision making or leadership. Women are also still underpaid and have their work, ideas and opinions questioned and denigrated by men. This is further exacerbated if, like Hildegard, a woman has physical or mental health issues, chronic pain, a disability or all three.

Overall, what can learn about gender regarding these aspects of Hildegard of Bingen’s life is that they dismantle the commonly held modern narrative that every medieval nun (and medieval women in general) was crippled and trapped by the patriarchal constructs surrounding them. Hildegard is a compelling example of how some medieval women, particularly nuns, navigated, explored, and created agency for themselves within the socio-cultural and religious confines placed on their gender, in this case regarding to the androcentrism and chauvinism surrounding religious visions.

Reference List:

Atherton, M (2001), ‘Hildegard of Bingen: selected writings’, in Saint, Hildegard, Selected writings / Hildegard of Bingen ; translated with an introduction and notes by Mark Atherton, Penguin, London, pp. i—undefined.

Dickens, A.J. (2009) ‘Chapter 2. Sybil of the Rhine: Hildegard of Bingen’, The female mystic : great women thinkers of the Middle Ages, I. B. Tauris, London, pp.25-28.

Newman, B (1985), ‘Hildegard of Bingen: Visions and Validation’, Church History, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 163–175.